Argonautidae

Argonauta

paper nautilus

Katharina M. Mangold (1922-2003), Michael Vecchione, and Richard E. Young- Argonauta argo

- Argonauta hians

- Argonauta boettgeri

- Argonauta nodosa

Introduction

Argonauts are muscular, pelagic octopods. Females secrete a thin calcareous "shell" in which they reside. Shells may reach a length of 30 cm (Nesis, 1982). The dorsal arms of females are modified with large, flag-like membranes that expand over the shell and are responsible for the secretion of the shell. Eyes are very large and webs very small. The mantle-funnel locking apparatus consists of knob-like cartilages (mantle) and matching depressions (funnel). Males are dwarfs.

Brief diagnosis:

An argonautoid ...

- with distal webs on arms I in females that secrete a calcareous shell.

- with a circular pit in the funnel locking-apparatus.

Characteristics

- Arms

- Hectocotylus without lateral fringes; penis not contained in special sac.

- Females with distal flag-like expansion of the web of the dorsal arms that contain shell-secreting glands.

Figure. Lateral view of a juvenile female (6.5 mm ML) Argonauta hians showing the web on arms I, equatorial South Atlantic. Drawing from Chun, 1910.

- Presence of external "shell" in females secreted by the dorsal arms. The true molluscan shell (i. e., stylets in most incirrates) is absent.

Figure. Side view of Argonauta sp., showing the expansion of the web (web presence indicated by their chromatophores) of the first arm, past the horn of the shell and over most of the shell surface, Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea. Photograph of living argonaut by Shai Enbinder; provided by Nadav Shashar.

- Hectocotylus without lateral fringes; penis not contained in special sac.

- Head

- Beaks: Descriptions can be found here: Lower beak; upper beak.

- Water pores: Water pores absent.

- Radula: First lateral tooth of radula not greatly reduced in size.

- Beaks: Descriptions can be found here: Lower beak; upper beak.

- Sexual dimorphism

- Males dwarf.

- Males dwarf.

- Funnel

- Funnel-mantle locking apparatus consists of a knob and pit.

Nomenclature

A list of all nominal genera and species in the Argonautidae can be found here. The list includes the current status and type species of all genera, and the current status, type repository and type locality of all species and all pertinent references.

Origin of the Argonaut Shell

An unusual feature of argonauts is the secreted shell that functions as a brood chamber. The "shell" is not homologous with the true molluscan shell as evidenced by its unique site of formation: the dorsal arms of the female rather than the internal shell sac as in other coleoids. Naef (1921/3) noted the remarkable resemblance of the argonaut shell to the shells of some of the abundant Cretaceous ammonoids and suggested that the argonaut shell evolved in the following way: Ancestral argonauts occupied empty ammonoid shells during the late Cretaceous. [Occupancy of molluscan shells by octopodids is common in the present day.] The octopod evolved glandular structures on the arms to repair the shell of the ammonoids after the latter had become extinct at the end of the Cretaceous. Eventually, the ammonoid shell was completely replaced by a secreted structure whose shape had been evolutionarily molded by the ammonoid shell. However, as pointed out by Young et al. (1998), a gap of about 40 million years exists between extinction of ammonoids and the earliest fossil record of an argonaut, and they suggest that the mold for the shell was from some other type of mollusc and that the resemblance to ammonoids is coincidental. The origin of the argonaut shell is a challenging problem and has important implications for understanding the relationships amoung groups of the Argonautoidea (Young, et al., 1998).

Life history

The male argonaut is a dwarf, about 10% of the length of the female. The entire third right arm is hectocotylized and carried in a special sac. At mating, the hectocotylus, which carries one large spermatophore, breaks out of its sac and then from the male body. The free hectocotylus invades, or is deposited in, the female's mantle cavity, where it remains viable and active for some time. The hectocotylus was first described as a worm parasitic on the female (Delle Chiaje, 1825).

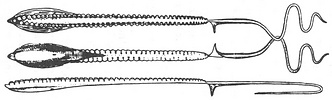

Figures. Lateral and oral views of male argonauts. Left, center - A 5 mm ML, apparently immature, male Argonauta hians from the equatorial South Atlantic. Drawings from Chun, 1910. In oral view the male looks like a 7-arm octopus. Right - A male Argonauta nodosa, off Australia, with the hectocotylus in a much larger sac is apparently mature. Photograph by Mandy Reid; provided by Mark Norman.

The female lives in a thin, calcareous, laterally compressed shell secreted by its dorsal arms. The shell is paper-thin and the animal is commonly called the "paper nautilus." The latter part of the name comes from similarly-shaped shell of Nautilus. The shell of the pearly nautilus, however, is the true cephalopod shell (i.e., the homologue of the molluscan shell) and not a unique evolutionary innovation like the "shell" of Argonauta (Naef, 1921-23).

Figure. Left - Lateral view of an Argonauta argo shell, Hawaii. Photograph by R. Young). Right - A collection of Argonauta nodosa shells from a swarm that washed ashore, Australia. Photograph by Mark Norman.

Embryonic development begins in the oviducts. Older embryos are attached to the inner region of the shell where they are brooded. The elongate egg stalks (extensions of the egg chorion) are woven together and attached to the shell apex on its inner surface. A female A. argo with a shell length of 88 mm was estimated to be carrying 48,800 embryos (Okutani and Kawaguchi, 1983). The eggs are very small (0.6 - 1.0 mm). Spawning is intermittent, and the brooding embryos can be seen to be in different stages of development.

The argonaut paralarva has a distinctive appearance as seen in the photo. The arms are very short and equal in length and are surrounded in their proximal half by a membranous collar or cuff (barely recognizable in the photograph) formed by the interbrachial membrane. The latter feature is found also in Tremoctopus hatchlings. The life-span is unknown.

Figure. Argonauta argo, young paralarvae. Left - Ventrolateral view captured in a plankton tow, Hawaii. Photograph by R. Young. Right - Side view. Drawing from Naef (1921-230. Note the lock and pit of the funnel/mantle locking-apparatus at the bottom of the photograph and drawing.

Habitat

Argonauts are pelagic in tropical and subtropical surface waters of all oceans and seas. Sometimes they are found in large swarms, but only rarely are they encountered nearshore. In the open ocean they are commonly found attached to jellyfish (David, 1965). While this unusual association between Argonauta spp. and jellyfish has long been known (Kramp, 1956; David, 1965) it was uninvestigated prior to the work of Heeger et al. (1992). The latter authors describe Argonauta astride the aboral (=exumbrellar) surface of a swimming jellyfish that it held with its lateral and ventral arms. Upon examination of the jellyfish they found about half of its aboral surface was damaged and large pieces of mesoglea were missing. Two holes, apparently bite marks were found in the center of this area and channels led from these holes into the gastral cavity of the jellyfish. They presumed the octopod used these channels to suck particles (food) from the gastral cavity. They also suggest that the association provided shelter or camouflage for the argonaut.

Figure. Two views of Argonauta argo atop the jellyfish, Phyllorhiza punctata. Photographs Copyright ©, Thomas Heeger, University of San Carlos, Philippines.

Males have been reported living within salps (Banas et al., 1982).

References

Banas, P. T., D. E. Smith and D. C. Biggs. 1982. An association between a pelagic octopod, Argonauta sp. Linnaeus 1758, and aggregate salps. Fish. Bull. U.S. 80: 648-650.

Chun, C. 1910. Die Cephalopoden. Oegopsida. Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Deutschen Tiefsee Expedition auf dem Dampfer "Valdivia" 1898-1899, 18(1):1-401.

David, P. M. 1965. The surface fauna of the ocean. Endeavour (Oxf.)24: 95-100).

Delle Chiaje, S. 1825. Memorie sulla storia e notomia degli animali. Senza Verlebre del Regno di Napoli. I.

Heeger, T., U. Piatkowski and H. Möller. 1992. Predation on jellyfish by the cephalopod Argonauta argo. Marine Ecology Progress Series 88: 293-296.

Kramp, P. L. 1956. Pelagic Fauna. P. 65-86. In: (A. Bruun, SV. Greve, H. Mielche and R. Spärck, eds.) The Galathea Deep Sea Expedition 1950-1952.

Naef, A. 1921/23. Cephalopoda. Fauna und Flora des Golfes von Neapel. Monograph, no. 35.

Nesis, K. N. 1982/7. Abridged key to the cephalopod mollusks of the world's ocean. 385,ii pp. Light and Food Industry Publishing House, Moscow. (In Russian.). Translated into English by B. S. Levitov, ed. by L. A. Burgess (1987), Cephalopods of the world. T. F. H. Publications, Neptune City, NJ, 351pp.

Okutani, T. and T. Kawaguchi. 1983. A mass occurrence of Argonauta argo (Cephalopoda: Octopoda) along the coast of Shimane Prefecture, Western Japan Sea. Venus 41: 281-290.

Young, R. E., M. Vecchione and D. Donovan. 1998 The evolution of coleoid cephalopods and their present biodiversity and ecology. South African Jour. Mar. Sci.., 20: 393-420.

About This Page

Katharina M. Mangold (1922-2003)

Laboratoire Arago, Banyuls-Sur-Mer, France

National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D. C. , USA

University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA

Page copyright © 2016 Katharina M. Mangold (1922-2003), , and

Page: Tree of Life

Argonautidae . Argonauta . paper nautilus.

Authored by

Katharina M. Mangold (1922-2003), Michael Vecchione, and Richard E. Young.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Argonautidae . Argonauta . paper nautilus.

Authored by

Katharina M. Mangold (1922-2003), Michael Vecchione, and Richard E. Young.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- Content changed 16 November 2016

Citing this page:

Mangold (1922-2003), Katharina M., Michael Vecchione, and Richard E. Young. 2016. Argonautidae . Argonauta . paper nautilus. Version 16 November 2016 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Argonauta/20204/2016.11.16 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site