Genetic Connections Between Organisms

Figure 1: A diagram of Mimi's immediate family. The passage of genes from parents to offspring is indicated by the green lines.

What do we mean when we say all organisms are genetically related?

We are all familiar with the genetic relationships between parents and their offspring. Kids usually resemble their parents and their siblings, because offspring inherit genes from their parents. But how do you get from these obvious, close genetic relationships to the more distant genetic relationships between species that are as different as daisies and elephants?

Consider an individual organism, a beetle called Mimi.

Like many other organisms, the beetles in Mimi's species reproduce sexually. This means that a parent passes on copies of half of his or her genes to each offspring. An offspring's genome then represents a combination of parental genes (Figure 1).

Mimi's family lives under a log, with a group of other beetles. New beetles are born every summer, and they live for about one year. So each year there is a new generation of beetles (Figure 2).

As you can see in Figure 2, Mimi does not only have two full siblings, but also two half siblings, since one of her parents produced offspring with another beetle.

Figure 2: The genetic relationships for the last three generations of beetles under Mimi's log.

Mimi's log is on a beach where there are a number of other logs housing groups of beetles. Members of Mimi's group sometimes meet beetles from these other logs and produce offspring with them. Occasionally, a beetle from another beach may fly in and participate in the production of offspring. Similarly, beetles from Mimi's beach may visit other beaches and mate with beetles there. Thus, Mimi is part of a larger population of beetles, extending over several beaches.

Figure 3: Genetic relationships for a segment of Mimi's beetle population over a number of generations. The last three generations of beetles under Mimi's log are shown in the blue frame.

The genetic connections among organisms within a sexually reproducing populations form a tangled web. Through generations, the genes of an individual are passed along a chain of offspring, i.e., children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and so on. Through the process of interbreeding, the individual's genes are combined at each step with the genes of other individuals. However, these genetic connections do not extend much between different species. Organisms generally look for mates within their own species, and so each species forms a reproductive community. As a result, each species descends through time as a bundle of genetic connections isolated from other such bundles formed by other species.

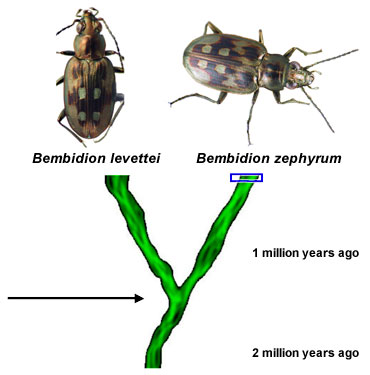

Occasionally, a species might be broken into two isolated reproductive communities. This could happen, for example, if some geographic barrier arose (e.g., a river broadening, sea levels rising, a mountain range lifting) that would prevent beetles from southern beaches from moving to northern beaches and vice versa. If such a barrier remained in place for a long time, the two isolated reproductive communities would evolve into separate species, and each would become its own isolated bundle of genetic connections. Something like this must have happened a long time ago when Mimi's species, Bembidion zephyrum, evolved from the ancestor it shares with its closest relative, Bembidion levettei (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Genetic relationships between two closely related species, Bembidion levettei and Bembidion zephyrum. Recent generations of beetles in Mimi's species are indicated with the blue frame. The arrow points to the common ancestor of the two beetle species.

If we went further back in the evolutionary history of Mimi's genetic lineage, we would see a sequence of beach beetle lineages splitting in two and giving rise to new species. Once the genetic ties between two lineages are severed, they are likely to diverge in their looks and habits, as ancestral features are modified independently in each species. So each species will be characterized by a unique set of traits, and species that are more closely related will generally be more similar to one another.

During the evolutionary history of beach beetles, some species would have gone extinct, while others, like Mimi's Bembidion zephyrum, would have flourished, producing a new generation of beetles each year. This process has resulted in an ever growing phylogenetic tree of species lineages, with some branches pruned in the past, and the species living today sitting like leaves at the tips of actively growing branches (Figure 5).

Figure 5: A phylogenetic tree of beach beetles. Some branches have gone extinct in the past, while others represent species living today.

Over the course of hundreds of millions of years, the splitting and subsequent divergence of lineages has produced the Tree of Life, which has as its leaves the many species of organisms we see around us today (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Genetic connections flowing along the branches of the Tree of Life.

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site